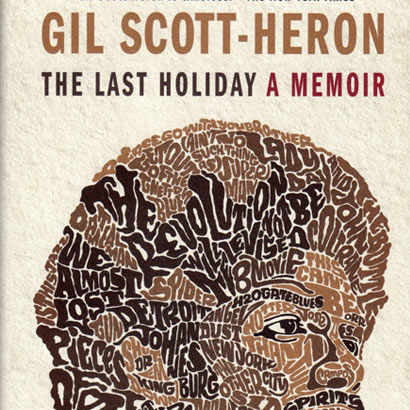

via Shook.FM (awesome website): “Gil Scott-Heron’s final opus, one that he was working on intermittently for the last two decades of his life, is not an album of music but a memoir. Autobiography isn’t quite the right word, because this book pulls down the shutters and closes shop in 1981, the mid-point in his fascinating life, leaving the artist in suspended animation.

He’s right at the height of his fame, and has just been asked to join Stevie Wonder on his Hotter Than July tour (see YouTube clip below). Bob Marley had initially been billed as the support act, but was hastily hospitalised when the cancer in his toe began spreading to the rest of his body. So Gil, who had originally been booked to play only the first dates of the tour in Texas and Louisiana, was drafted in for the whole 16-week tour.

The tour climaxed with the Rally for Peace on January 15 1981 in Washington D.C. Organised by Stevie Wonder to support the campaign to have Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday recognised as a national holiday, that Rally, and the song accompanying the campaign, ‘Happy Birthday’, forced the politicians’ hand. In a neat instance of dramatic irony, it was Ronald Reagan who signed the national holiday into law in 1983.

Reagan, or ‘Raygun’ as he was fond of calling him, was the butt of a stream of jokes by Gil Scott-Heron, the poet and provocateur who held up a mirror to America and told people what was really going on. He was the thorn in side of the politicians and he was the poet of the ordinary folk, singing about their hopes and dreams. But to actually change the statute books, irrevocably – like Stevie had set out to do – that, for Gil, was the point of the struggle.

What a previous generation, the likes of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rosa Parks, had set in motion, drove Gil to write, to teach and to perform. And when Gil finds himself on stage in the National Mall, where Martin Luther King, Jr. had been in 1963 to deliver his ‘I Have A Dream’ speech, he looks up: “And I could see for the first time, I could see what this brother had seen long before, what really needed to be done.”

How he got to that point there is what The Last Holiday sets out to tell. It begins in Jackson, Tennessee where Gil was raises up by his grandmother, Lily Scott – “[Jackson] was where I began to write, learned to play piano, and where I began to want to write songs.” The picture Gil paints of his grandmother is of a remarkable Southern matriarch, church-going, upright, and though never educated herself, a woman who had insisted on teaching Gil to read from a young age. They would pick out chapters from the Bible every night, or in the Chicago Defender pore over articles featuring Jesse B. Semple, the character created by Langston Hughes. Segregation was still in force in the south, and after the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case, Gil was one of the first students to be admitted to a white school in November 1962.

Much of the first half of the book is given over to the education that Gil receives, moving with his mother to New York, where he gains a scholarship to the prestigious private school, Fieldston, and then to Lincoln University, the alma mater of Langston Hughes and Thurgood Marshall. Marshall was the first African-American justice of the Supreme Court. It was his victory in the Brown v. Board of Education that started the path to desegregation and left an indelible mark on the mind of the young artist.

But by the time he gets to Lincoln, though, it’s no longer quite the same institution. The school has become a co-ed that year, and Gil buries himself in the library. Much to the dismay of his professors, he insists on taking a sabbatical after his first year to write The Vulture, a murder mystery novel in the mould of Chester Himes’ stories. There’s a particularly evocative scene in the memoir when Gil recalls working in a dry cleaners on the outskirts of the university campus, typing away at his novel and getting college friends to read his work. The publishers agree to take on The Vulture, and Gil returns to Lincoln with a book deal aged just 21.

During his time at Lincoln he also meets Brian Jackson. It would be their musical partnership that would create so many timeless albums, from Winter In America right through to Bridges in 1977. And Gil’s already demonstrating his political colours when he closes down the university in protest over inadequate medical facilities after a friend dies on campus.

What the reader can’t help but notice is the unbridled confidence and the razor sharp wit of the young Gil Scott-Heron (“I’ve always been a lot too arrogant and a little too fuckin’ wise,” he would say on Don’t Give Up). He waltzes into publishing houses to demand publishing deals, or into Flying Dutchman where Bob Thiele, a teenage hero of his who had produced albums for John Coltrane, offers him a contract. He befriends with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Stevie Wonder often turns up unannounced to his shows, and there are scores of other famous encounters, from Sydney Poitier to Michael Jackson.

In the Last Holiday, the makings of Gil Scott-Heron are plain to see. As listeners of his music will know, the subject of his art had always been the world around him, regular folk scrambling together a living, and he tried to give them hope. ‘It’s Your World’, he told them. But in Gil’s late career, especially on Spirits in 1994 and that final album for XL in 2010, there was a return home. On that final record too he evoked Jackson, Tennessee and Grandma Lily Scott.

Still, for all he reveals, Gil leaves many stones unturned. There are those last 30 years, which are elided in a couple of inconclusive chapters; there’s little about the music itself, how the songs were written, what they meant. The story also tends to jump around in time, each chapter, in its brevity, has an almost parable-like quality. When the publisher writes at the end of the book, “We are greatly indebted to Tim Mohr, whose editing skills and commitment to the project have resulted in The Last Holiday reading as smoothly as it does,” you suspect that publishing The Last Holiday has been no holiday for those involved.

On reflection, what we’re left with is fragments, “jagged jigsaw pieces”, to quote a line from one of his well-known songs. His memoir may not captivate the casual reader, but for those who have been touched by the artist, either live or on record, The Last Holiday is the final chance to spend time in the company of a man who may not have changed the statute books, but whose influence is incalculable, wrought as it is on the hearts of those who heard his message.”

The Last Holiday by Gil Scott-Heron is published by Canongate.

No Comment