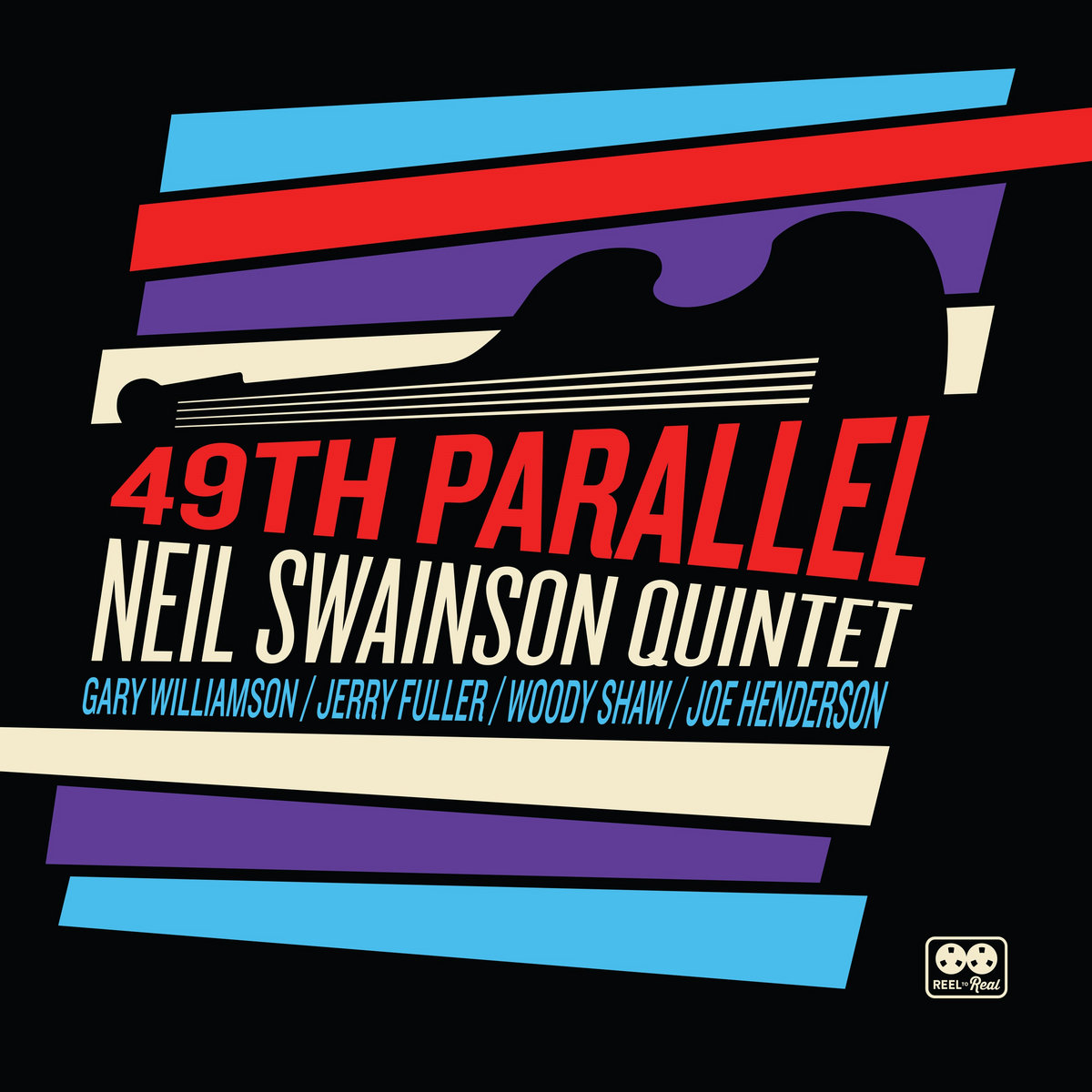

Bassist Neil Swainson’s rare and sought after recording, 49th Parallel, is finally getting a much needed re-release (first time on vinyl) on Cellar Live’s Reel to Real imprint and la reserve Records.

The debut and only album from one of Canada’s most important bassists, Swainson features tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson and trumpeter Woody Shaw along with Jerry Fuller on drums and Gary Williamson on piano. The album was Woody Shaw’s last studio recording.

On 49th Parallel, Neil Swainson matched the right musicians with the right music and then had the wisdom to let things unfold organically, allowing these artists to play to their estimable strengths. The result is a complete and satisfying artistic statement.

Cory Weeds: When did you move to Toronto?

Neil Swainson: February of 1977

When did you start playing with Woody Shaw?

Neil Swainson: I played a few gigs with Woody in the early to mid-80s. It was 1987 when we recorded 49th Parallel. I had started working with Woody at Bourbon Street. Jerry Fuller, Gary Williamson and I were the rhythm section, which became the rhythm section on the record. Bourbon Street was a club, much like the Cellar or Frankie’s, where local rhythm sections often played with visiting American or European artists. At that time, in the mid-80s, Jerry Fuller and I worked quite a bit at Bourbon Street. Woody Shaw was one of the guests at that time and he came up by himself. So we worked for a week at Bourbon Street, and then he had a week at a club called the Cock and Lion in Ottawa, which was in the Château Laurier. We went up and played with him there as well. We played two weeks in a row pretty much, the same guys, and we got along pretty well.

How did the Joe Henderson thing come together?

Neil Swainson: I hadn’t actually worked with Joe before the recording. I did after, but at that point I had not worked with him. It started when I was talking with Kate Roach about doing this recording project. I had written a bunch of tunes, played them on various gigs, and demo recorded them. I said, “Ideally, I’d like to do this with Woody Shaw and Joe Henderson, although I don’t know Joe Henderson.” Kate said, “I’ll reach out to him and ask him, and then negotiate and all that stuff.” She did that and I’d never met him before. Once he knew that Woody was onboard, I think he was more inclined to say yes, but he didn’t know who we were.

What happened next was we had a night booked at a club called the Bamboo in Toronto, with the same quintet that was going to go in the next couple of days and record. Woody showed up and Joe Henderson didn’t. We didn’t hear anything from Joe. At the last minute, we called Sam Noto, who happened to be living in town, and actually had a great night. Wonderful trumpet playing and free-spirited music. And Joe never sent word. He just didn’t show.

They called him the phantom. I said, “Woody, Joe didn’t show up.” And he said, “Oh, that chicken shit motherfucker.” Because he said that shit used to happen to them all the time. When they worked with Joe, with George Cables, Stanley Clarke and Lenny White, they’d show up in cities and Joe wouldn’t show up so the band would be stranded. They’d have to find their own way home from there. It happened many times to them, right? He knew this shit was happening. But what Joe had done is he had booked another gig in Chicago that ran two nights and this was the second night. He’d just take the better offer. So he missed the gig and he missed the first day of recording too. That’s why there’s some quartet tunes on the record. It was supposed to be all quintet.

We went into the recording studio with Woody, Gary, Jerry and me. We did my tunes, and I picked the ones where the melody was in unison so we could get through without missing a harmony part. That was fine, and then around midnight of that first day of recording, I got a phone call at home. It was Joe Henderson. He said, “Hey Neil, it’s Joe.” I’d never talked to him before. I said, “Joe, where are you?” He replied, “I’m in town, I’m at the hotel.” Then he asked about where to get something to eat. I said, “Go to the front door, turn left and walk along Dundas. You’ll hit Chinatown in about five blocks.” Joe said, “OK, I’ll see you tomorrow.”

We recorded with Joe in one day, and that was the first time I’d ever met him. It was a trial by fire. But he was great. He was thoroughly professional, a great guy, very intelligent, very methodical. He’d sit down at the piano and I’d show him the piano parts or the lead sheets and he’d go, “Is this what you mean?” And he haltingly played through it. He internalized it that way. Then when he played it, he just nailed it. Everything was a first or second take with him. We did all his parts in one day. It was great. After that, I did some more work with him. With Jon Ballantyne, we did a recording and a tour of Western Canada.

I read that at the time of the recording, Woody Shaw’s eyesight was very compromised and he had to learn all the music by ear. You taught him all the parts that way?

Neil Swainson: That’s correct. Woody couldn’t see anything because he had retinitis pigmentosa. He came to my house and I just played him the trumpet parts on the piano. Woody played them right back and then he memorized them. He went in the studio the next day and still had them in his brain. Woody was amazing. He had the best ears I’ve ever encountered. There are lots of people I know with great ears, but his were amazing. I did a clinic with him one time and he said, “OK, somebody go to the piano and play 10 notes.” He named all of the notes from the bottom to the top instantly. He knew everything that was going on at all times.

Can you talk about your rhythm section mates in this particular band, Gary Williamson and Jerry Fuller?

Neil Swainson: Gary Williamson was a great piano player, who I didn’t work with as often as I would have liked. But at the time, he was one of the pianists – like Bernie Senensky or Don Thompson – who likely would get called for a gig like that. Gary was a great choice. He was a great and really interesting piano player, and really modern. Another guy with perfect pitch and wonderful ears. That was one of the first times that I played with him for a couple of weeks in a row. Then we subsequently played with Woody and did this recording.

Jerry Fuller and I had worked a lot together, especially at Bourbon Street with many people, from Wild Bill Davison to Woody Shaw and Joe Henderson and swing guys and singers. You name it, we did it. Jerry did everything. He and I were like brothers. We did so many gigs together that it was like falling off a log. He was a great drummer in the Philly Joe Jones tradition. He could always hear the melody. He knew a lot about harmony. He knew the songs. If we didn’t know a song, he’d hum the bass notes to you. He was a great rhythm section mate. I learned a lot from playing with Jerry, especially when I was in my early 20s and we were playing with pretty well-known people.

You were in your mid to late 20s and you were bringing up Joe Henderson and Woody Shaw. That must have been something, working with those two guys. Do you remember what that feeling was like?

Neil Swainson: I had been working with Woody for a few years. I was quite comfortable with him because I’d been to New York with him a bunch of times, and to Europe. It was just the Joe Henderson part – that was the unknown. The fact that he agreed to do it in the first place was like, holy shit, this is the big time now. I thought, “I’ll just do the best I can.” Nerves and everything dissipated when you start playing. Plus, I’m working with Gary and Jerry who had worked with a lot of big people and it wasn’t an issue whether it was going to be good. Jerry’s going to carry it, and Gary and Woody. It’s going to be great no matter what. I just had fun, really. It was just initially daunting.

You’re not just the bass player in this group. It’s your band, it’s your tunes, you’re the leader. Got to be some added pressure there?

Neil Swainson: Well, it didn’t stop me. It didn’t hold me back. I had my friend Pat Coleman who was producing it and that was a relief because I knew him very well. Kate Roach was executive producer and she’s a dear friend of mine. She was responsible for getting it off the ground financially and organizationally. I was in good hands, and I wasn’t too concerned with having to deal with all the minute details.

Let’s talk about Kate, who’s also become a good friend of mine. What was her role? What did she contribute?

Neil Swainson: At the time she was a jazz fan and Jerry and I, and a bunch of us, all knew her. We’d have drinks at her place or go out for dinner. She just became a really good friend. When I mentioned that I wanted to do this project, she said, “Let’s make it happen. I’ll call some people and I’ll try to raise some money.”

We had business meetings with some friends of hers, and people agreed to pledge money. I didn’t have any money. She organized all that stuff. She’s a very astute businesswoman, as well. She’s had many careers doing different things. She completely takes charge in that situation and says, “OK, let’s do this. We’re going to have a meeting tomorrow and have lunch and talk about the details. We’ll talk about what you’ll need and how much it’s going to cost. Then we’ll call the studios and find out prices.” So she took care of all that stuff. It wouldn’t have happened without her, for sure. Guarantee you that.

Do you have any memories of how the album was received? Did you feel it did a lot for your career? Did it open up some doors?

Neil Swainson: I think in the long term it did a lot. In terms of name recognition, people who had the record knew who I was. But in the short term, it didn’t necessarily do a lot. I didn’t have people calling me to tour Europe with my own band, because I couldn’t have done that with Joe and Woody. It was one of those things, slow developing.

It didn’t get nominated for a Juno or anything. It was released on Concord Records and they didn’t think to submit it and I didn’t care. But it did fairly well in sales. I got royalties for the tunes and number of records sold and everything. For a jazz recording by a fairly unknown person – I was working with George Shearing by the time it came out – I got lots of good reviews in various publications.

This wasn’t a standard record deal in which Concord approached you and said, “We want you to make a record. We can offer you X amount of dollars.” The Concord thing came after you recorded it, am I correct?

Neil Swainson: It did. What happened was I was on a Concord Fujitsu Festival tour with George Shearing. I had started working with George recently. Don Thompson had left George’s band because he didn’t want to travel any more. George got Don a green card and he couldn’t reapply for another bass player to get a green card. George said, “I’ll hire you for the overseas stuff, but for the States I can’t get you a green card because I just went through the process and they’re not going to let it happen.” Then I was talking about that with Carl Jefferson, who was the founder and president of Concord Records. He said, “Oh, I’ll get you a visa. I’ll call my secretary Joan and we’re going to get my Congressman on it and you’ll have a visa in no time.” And sure enough he did all of that. I got a three-year visa a month later.

So, while we were in Japan, I talked about this recording, which we hadn’t released because I didn’t have a label. We were just shopping it around. I told Carl that Woody Shaw, who had passed away the year before, was on it along with Joe Henderson. I said, “I think it’s great. There’s great Woody Shaw and Joe Henderson on there.” And he said, “I’d love to hear it. It would be good to put out a record as a tribute to Woody Shaw.” Carl said he’d put it out. Not only did I get a visa to work with Shearing, but I also put out my record the same week. So Carl Jefferson was really helpful in that respect.

Did Carl and Concord see the importance of the recording as Canadian content?

Neil Swainson: I don’t think it was released in Canada as Canadian content particularly. It was just released like all the other Concord releases were. I don’t think they paid too much attention to the Canadian market, other than as another place to sell records. It wasn’t the typical Concord music, either.

When is the last time you listened to it?

Neil Swainson: Oh, I haven’t listened to that thing in years.

How do you think it stands up to the test of time?

Neil Swainson: It’s almost 30 years it’s been out there. The playing is very good, especially Woody and Joe, and Jerry and Gary as well. Whatever I think about my own playing, I’m not unhappy with the recording. I’m glad it came out at all.

If I’m not mistaken, I think this is your only album as a leader. It’s pretty hard to top that, but is it because another opportunity hasn’t come up?

Neil Swainson: That’s basically it. I could never afford to pay for another one myself and I was busy enough as a sideman, so I wasn’t really pursuing a career as a leader. I didn’t feel it was like absolutely necessary. I’ve got a family and other things that are prioritized before I’m going to spend my own money on a project that would marginally affect anything or anybody. But I’m glad to have an opportunity to release it again.

Yes, and after the release of this, we’ll take you and a quintet into the studio. We’re going to go into the studio once we can get everybody together. It’s going to be a nice companion recording to the re-release of 49th Parallel.

Neil Swainson: In fact, I ran into somebody last night who said, “Man, you know that record you made? It would be so great if you re-released it.” I said, “Man, you wouldn’t believe how coincidental that is because Cory is going to do that.” I’m grateful for the opportunity.