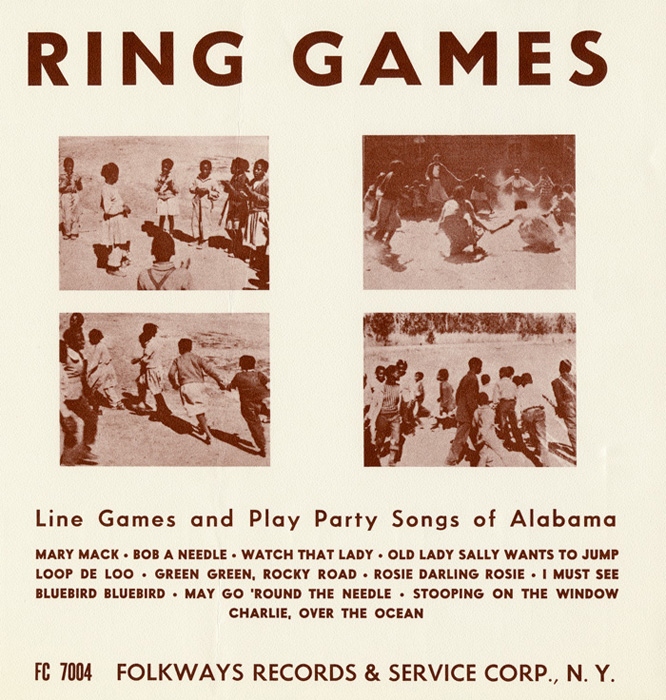

Forgotten Treasure: Ring Games “Line Games and Play Party Songs of Alabama” (1953)

The last few years have brought many changes into my life. Getting older, I’ve taken a more serious approach to marriage and starting my own family. But, how would my wife and I be raising this family of ours. What type of diet would we consume? Would we be a practicing religious family? Where will we live; what kinds of schools will our children attend? These questions, and so many more, fill my brain when I think about big life decisions to be made in the next few years. Then I reflect back on my childhood and try to locate the mindset of my mother, elders, and ancestors. How difficult it must have been for African parents to find a space for themselves within a still developing system that did not want them, save for “laborers”, at all.

Since the abolishment of the “peculiar institution” in 1865, Black Americans have created and adapted ways of creatively being social, learning, and passing the time. Examples of these can be found in Emma (1919-2005) and Harold (1908-1996) Courlander’s collection of field recordings entitled Ring Games: Line Games and Play Party Songs of Alabama (Folkways Records, 1953). Being familiar with some of these songs, or variations of them, what these recordings represent are not only folk songs created/ used by Black children for the above listed purposes, they also stand as pillars of familiarity in the childhoods of many Black Americans born before the advent of the internet and social media. Growing up in 1980s West Baltimore, songs and games like these played as background music for me and my peers. Executed primarily by young Black girls, these songs were passed down from generation to generation just like the skills/ technique of watching children, learning hymns, and braiding hair. It was within these gifts, and so many more, that Black girls turned women became and stayed the keepers of family/ community folklore, knowledge, and wisdom. To some readers these songs might seem “outdated”, but for those of us Black folk who remember our world pre-gentrification and pre-www.whatever.com, these songs represent a part of the backbone that holds our past and hopes for the future together.

The 10” recording starts off with what is probably one of the most well known folk related songs/ games ever. “Mary Mack”, more commonly known as “Miss Mary Mack”, has taken many tempo changes over the years and is typically performed while doing chest-to-hand clapping motions or jumping rope (especially within the high art of Double Dutch). In fact, the tune is so popular that it has its own Wikipedia page… seriously. It, and the rest of the songs on this collection, are short and made to be sung in repetition until another song was chosen (at least that’s how they did it on the playground/ block when I was coming up).

“Loop De Loo”, also known as “Loobie Loo”, is a variation of “Hokey Pokey”, apparently having roots as a British folk dance. If this is the case, the song/ game may have been introduced to enslaved Africans by British/ white American children (but again, this is just my guess as the liner notes make no mention of this). One of the things that the listener will notice after a few tunes is the grittiness and the repetition of the songs. Most of the material doesn’t reach the 2-minute mark and it becomes very apparent that the songs share a basic familiarity with worksongs, blues numbers, and gospel tunes. There is a basic verse, a reframe, and sometimes a call and response structured chorus. Though this record probably appealed more to schoolteachers and parents, ethnomusicologist should be, responsibly enough, able to point out that these songs not only demonstrate the basic elements of American music, they also are a continuation of various styles of community based singing/ playing in West Africa.

Besides the opening song, the piece that fascinates me the most is “Rosie Darling Rosie”. It works like a song of composed by those enslaved planning to escape to Baltimore. Historical, during some periods of enslavement, Baltimore was an easier place to start a new life outside of slavery. There were methods of getting to further destinations, and even if one decided to stay, the laws concerning Blacks were much more relaxed than those of the deeper South.*

It pulls at my heartstrings to hear these songs at this point in my life. Growing up with relatives who were born just after the period known as Reconstruction, they coincide not only with stories of the deep South my grandparents used to tell us about, but they also serve as a reminder to how I want my kids to be raised. I want my Black girls and boys to know every single aspect of their history and never want them to be ashamed to be descendants of survivors. Listening to these children sing in 1953 gives me clarity, and also mad abundance of life. My only regret is that I didn’t listen to them closer being sung in real time by the wonderful little Black girls I spent my childhood with. Hopefully my daughters, and those of likeminded Black folk, can bring this tradition back from the grave that it is quickly approaching.

*For those interested in that period of Baltimore’s history, I suggest reading Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1895).

Buy Album

No Comment