Via ScienceMag: “When jazz legend John Coltrane first heard Charlie Parker play the saxophone, the music hit him “right between the eyes,” he once said. According to neuroscientists, Coltrane was exactly right. When we hear music that we like, even for the first time, a part of the brain’s reward system is activated, a new study has shown. The region, called the nucleus accumbens, determines how much we value the song—even predicting how much a person is willing to pay for the new track.”

“It’s a lovely, lovely piece of research,” says music psychologist David Huron of Ohio State University, Columbus, who was not involved in the study. The results will help scientists understand why humans attach so much value to abstract sequences of sound waves. “Music is one of those oddball things,” he says. “It’s not at all clear that it has any sort of survival value.”

A favorite song, whether a power rock anthem or a soulful acoustic ballad, evokes a deep emotional response. Neuroscientist Valorie Salimpoor recalls once listening to Johannes Brahms’s “Hungarian Dance No. 5” while driving. The music moved her so profoundly that she had to pull over. Intrigued by the experience, Salimpoor joined Robert Zatorre at McGill University’s Montreal Neurological Institute in Canada to study how music affects the brain. In 2011, she and Zatorre confirmed that dopamine, a reward neurotransmitter, is the source of such intense experiences—the “chills”—associated with a favorite piece of music. They showed that listeners’ dopamine levels in pleasure centers surged during key passages of favorite music, but also just a moment before—as if the brain was anticipating the crescendo to come.

Salimpoor, now at the Rotman Research Institute in Toronto, Canada, wondered if the response was due to the music itself or to participants’ emotional attachment to it. She recruited 19 volunteers, 10 men and nine women aged 18 to 37, who shared self-reported musical tastes. “Indie” and “electronic” proved most popular. Salimpoor played 30-second samples of 60 songs they’d never heard before. Within an iTunes-like user interface, the volunteers then bid on how much they’d be willing to pay for each track, up to $2. To make the experiment more realistic, participants used their own money and received a CD of their purchased tracks at the end of the study.

Live Chat: Can We Keep Our Genomes Secret? Thursday 3 p.m. EDT

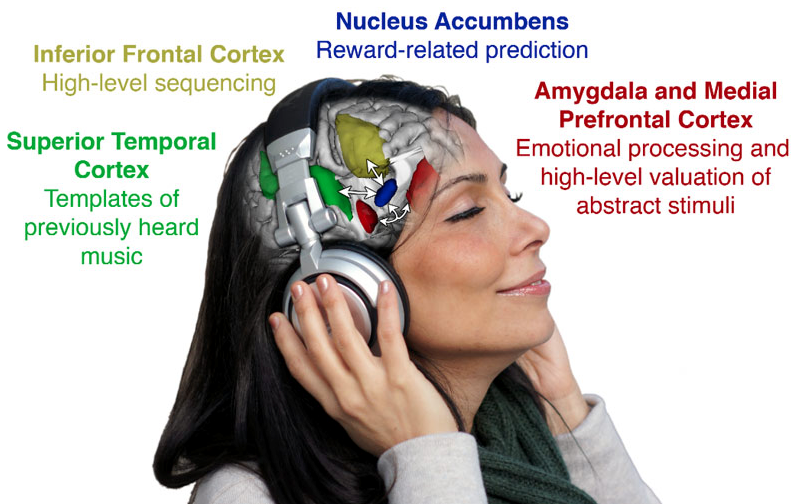

Salimpoor monitored how the volunteers’ brains reacted to the music using MRI. Multiple brain regions activated when they discovered a new favorite song, but only activity in the nucleus accumbens was well-correlated to how much the participants were willing to pay, she and colleagues report online today in Science.

The nucleus accumbens is believed to be responsible for pleasant surprises, or “positive prediction error,” as neuroscientists call it. Our brains are well-suited to using patterns, such as the structure of music, to predict the future. “We’re constantly making predictions, even if we don’t know the music,” Salimpoor says. “We’re still predicting how it should unfold.”

These predictions are based on past musical experience, so classical fans will have different expectations than punk devotees. But when the music turns out better than the brain expected, the nucleus accumbens fires off with delight. Salimpoor concluded that the nucleus accumbens works in concert with pattern recognition and higher-order thinking centers to assign value to music.

Vinod Menon, a cognitive neuroscientist at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, wonders if the presence of lyrics in some tracks introduced confounding variables. “We don’t know if it’s the musical sounds or the linguistic components that drove some of these effects,” he says. Salimpoor responds that previous research showed similar brain effects using only instrumental music. Lyrics, she says, did not appear to skew listener’s purchasing decisions.

Next, Salimpoor will investigate another area of the brain, the superior temporal gyrus. She aims to discover how this region, which stores a record of the sounds we’ve heard, shapes our future musical preferences. Eat your heart out, Pandora.

No Comment